Shabti Dolls: An Afterlife Changing Discovery!

- tsugumi8

- Jan 30

- 7 min read

Have you ever visited an exhibition to see a specific artwork or artefact, only to feel utterly unimpressed when standing before it, while some obscure piece gives you the biggest AHA MOMENT of your life? Perhaps you’ve stood before the Mona Lisa, elbowing your way towards her, jostling with people from all the seven continents only to exclaim: ‘I thought it was bigger!’, to be later captivated by something you hadn’t even anticipated. Can you relate? That has happened to me multiple times, not just at the Louvre but also on my latest trip to Modena. Here, I expected to be blown away by Tintoretto’sEpisodes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1541-42). Instead, I stumbled upon an afterlife-changing discovery: the Shabti dolls, which not only changed my perception of the Egyptian afterlife but also revived a long-forgotten love for this ancient culture. Are you intrigued? Then, do keep on reading!

Something Unexpected

Modena is a cultural hub in full bloom, where past and present mingle harmoniously. Here, you might wish to visit the Romanesque cathedral of San Geminiano by Lanfranco with its low reliefs, masterfully sculpted by Wiligelmo or the city’s cultural institution par excellence - the Estensi Gallery. I did see all the Italian city had to offer, but what stayed with me were some rather modest yet exquisitely manufactured sculptures created more than 3000 years ago, seen out of chance. Yes, out of chance… I saw them exhibited at the temporary exhibition Riflessi d’Egitto - Fascinazioni e tracce nelle raccolte Estensi - on display until May 4, 2025 - only because I had missed the bus to see Pavarotti’s house! However, thanks to this holiday’s twist, I became acquainted with the Egyptian artefacts collected by the influential Este family, whose interest in Ancient Egypt can be traced back to 1584, when fragments of an Egyptian sculpture were recorded in one of their statue’s inventories. This is still part of their collection and of the exhibit.

The Este Family and Their Passion for Egypt

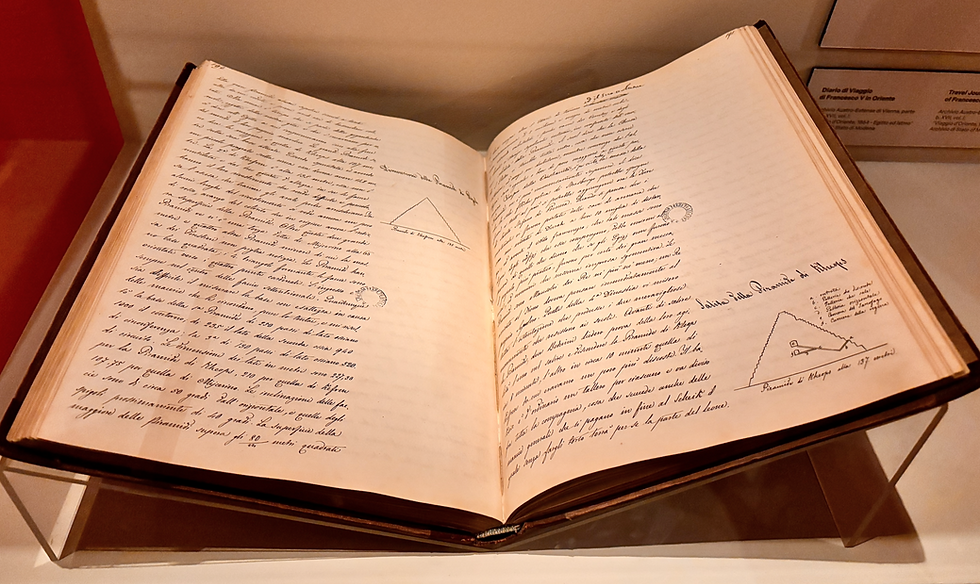

The exhibition, curated by Maria Chiara Montecchi, wants to open a window into Ancient Egypt and locate each piece's importance in the Este family’s historical tapestry. The Este were great art collectors who gave in to Egypt's allure. However, this is a little-known aspect of this family, who began to collect artefacts from the late 16th until the late 19th century. Duke Francesco V of Austria-Este took this long-established family’s passion one step further by visiting Egypt and logging his memoirs in a travel journal – a piece of remarkable beauty displayed at the exhibition. The display showcases more than 150 artefacts, including statuettes, amulets, stelae, and a sarcophagus from the Ptolemaic period (305 - 30 BCE). However, as the purpose of the exhibition is twofold, these artefacts are juxtaposed to depictions of the members of the Este family and their possessions, successfully fitting these artefacts into the family’s history, thus creating a continuous narrative.

Shabtis and the Egyptian Afterlife

Some of the artefacts on display caught my attention: doll-size statuettes shaped like Egyptian sarcophagi made of painted limestone, known as shabti dolls, created during the New Kingdom (1539 – 1077 BCE) and preserved in generally good condition. You may be wondering: what was their uniqueness? However, before I address this question, I should briefly explain what the Egyptians believed occurred in the afterlife. The Egyptians thought that the ever-after mirrored life on earth. Thus, work was still part of this reality and was a duty everyone was obliged to fulfil, even the pharaoh. Thence, once Anubis weighed the heart of the deceased, which had to be as light as a feather for the soul to enter the afterlife, the spirit would be free to cross Lily Lake and reach the Field of Reeds – an idyllic version of Egypt, where the departed could reunite with their lost loved ones, animals, and possessions. However, in this same field, they also had to toil for the rest of eternity, which, as you may agree, wasn’t a particularly appealing thought.

A Unique Function

Now, let us address the earlier question: What made Shabti dolls unique? Their uniqueness lay in their capacity to be activated through a spell, either spell 472 from the Coffin Text or spell 6 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, to be called by the deceased and work in their stead. They were, in fact, buried with the dead so that once in the afterlife, the deceased's soul could use them. However, these dolls had some downsides. The same shabti could not be used for more than a day, meaning that if one did not want to work for the entire year, they had to have 365 dolls. Unfortunately, this wasn’t possible for many because even if shabtis had varying costs, depending on the material – typically, faience, wood or stone – and the level of finish, these were still not accessible to poor people, who could at most afford to buy two or three.

A Sign of Social Status

Thus, although both wealthy and poor individuals were equally summoned by Osiris to labour for him in the Field of Reeds, what distinguished them was the number of shabtis that they owned, which translated into more or less days of idle in the afterlife. A rich person with a good collection of shabtis could comfortably repose beneath a palm tree, stroking their deceased cat. At the same time, a farmer had to toil under the scorching sun, harvesting wheat, and have two or three days of rest in a year for the rest of their eternity. Not a pleasant perspective, is it? However, since the number of shabtis with which the dead were buried is indicative of the departed status, archaeologists use them to ascertain the social status of their owners. Additionally, archaeologists have observed that these dolls underwent various changes from their initial emergence (1539 – 1077 BCE) up to the Roman Period (30 BCE – 395 CE).

The Evolution of Shabti Dolls

As said above, to begin with, shabtis were perceived as the afterlife workforce – special dolls that, through some formulas, could be brought to life and work in the deceased stead. However, during the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069 – 747 BCE), something changed, and they began to be conceived more as slaves than helpers. Archaeologists have deduced this because, in this period, a new doll emerged. In fact, while in the previous period, shabtis were only portrayed holding the tools that they would use in the afterlife, such as sickles or hoes, starting from the Third Intermediate Period, a ‘supervisor’ doll appeared, and this holds a whip, meaning that this doll was appointed to oversee the work of the shabtis who laboured. As revealed by archaeological excavations, one of them oversaw the work of ten shabtis. However, they disappeared in the Late Period (664 – 332 BCE), marking the last shabtis shift, which were once again considered helpers.

Shabtis Legacy Today

Historically, the perception of shabtis has changed over time, but what is their legacy today? Alongside scarabs, shabtis are among the most common artefacts from Ancient Egypt, creating opportunities for collectors to purchase them. Thus, we can say that the shabtis market has evolved along with their function, but it has never ceased to exist! In ancient times, temple workshops held the shabti dolls monopoly, but now they are sold at auctions starting at prices that either I or you could afford if, rather than paying our monthly rent, we suddenly decided to redirect that money towards this interesting purchase, or if that does still sound like a lot of money to you, the British Museums sells copies for only £ 38.00 each. Investing in a shabti seems somewhat promising, and their prices are guaranteed to rise from 8% to 10% each year. A fragment of Seti I – father of Ramses II, was sold in Paris for €740.000. That’s quite a staggering number, isn’t it? So, unfortunately, this is what these afterlife helpers have turned into today: a coveted item for collectors.

Final Reflections

Perhaps collecting shabtis today isn’t all that different from collecting them in the past. After all, I was only able to come across them because the Este family began collecting them a few centuries ago, and thanks to them, I was able to revive my interest in Ancient Egypt. When I first entered the Estensi Gallery, I never thought I would conduct such extensive research on these artefacts. Exhibitions are like this, though, aren’t they? You never quite know what will capture your attention and the history you will uncover behind a seemingly modest item. I hope I have sparked your curiosity with this post enough for you to want to learn more about shabti dolls. However, before you go, I have a question: what are your thoughts on the current shabti dolls market, and would you consider buying one?

Written by

Gabriella Sentina

30.01.2025 Author's notes

I apologise for not sharing any new content in the past two weeks. I've had to deal with a bit of writer's block and have also been conducting research for an important new article that you'll soon see here. Thank you for your understanding and support. G.S.

Comentarios